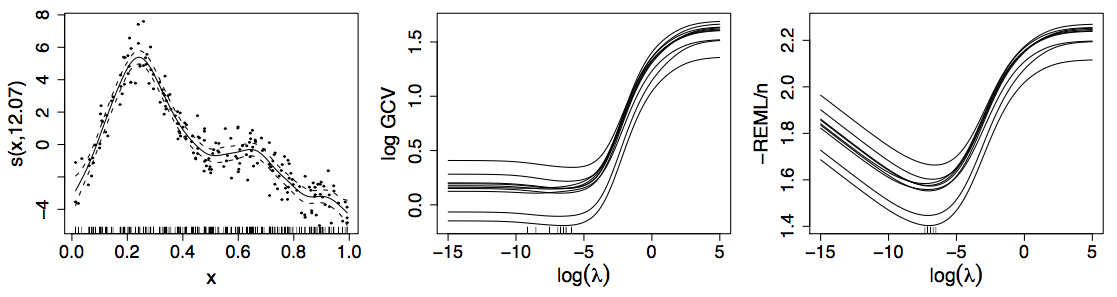

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # MT612 - Advanced Quant. Research Methods ] .subtitle[ ## Lecture 4: Generalized Additive (Mixed) Models ] .author[ ### Damien Dupré ] .date[ ### Dublin City University ] --- # References - Slides created by Gavin Simpson: https://fromthebottomoftheheap.net/slides/gam-intro-webinar-2020/gam-intro.html - He has a great webinar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgw4cu8hrZM - Interactive course: https://noamross.github.io/gams-in-r-course/ --- class: inverse, mline, center, middle # Not Everything is Linear --- # HadCRUT4 time series <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-1-1.png" width="864" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ### How would you model the trend in these data? --- # Linear Models `$$y_i = b_0 + b_1 x_{1i} + b_2 x_{2i} + \cdots + b_j x_{ji} + e_i$$` `$$e_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$$` Assumptions: 1. Linear effects are good approximation of the true effects 2. Distribution of residuals is `\(e_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\)` 3. Implies all observations have the same *variance* 4. Residuals `\(e_i\)` are *independent* An **additive** model address the first of these --- class: inverse, mline, center, middle # GAMs offer a solution --- # Fitted GAM - Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) are a flexible and powerful class of regression models that can capture non-linear relationships between the response variable and the predictors. - GAMs take each predictor variable in the model and separate it into sections (delimited by 'knots'), and then fit polynomial functions to each section separately, with the constraint that there are no kinks at the knots (second derivatives of the separate functions are equal at the knots). - Since the model fit is based on deviance/likelihood, fitted models are directly comparable with GLMs using likelihood techniques (like AIC) or classical tests based on model deviance (Chi-squared or F tests, depending on the error structure). - Even better, all the error and link structures of GLMs are available in GAMs (including poisson and binomial), as are the standard suite of lm or glm attributes (resid, fitted, summary, coef, etc.). --- # Fitted GAM <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-2-1.png" width="864" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Generalized Additive Models <br />  .references[Source: [GAMs in R by Noam Ross](https://noamross.github.io/gams-in-r-course/)] ??? GAMs are an intermediate-complexity model * can learn from data without needing to be informed by the user * remain interpretable because we can visualize the fitted features --- # How is a GAM different? In LM we model the mean of data as a sum of linear terms: `$$y_i = \beta_0 +\sum_j \color{red}{ \beta_j x_{ji}} +\epsilon_i$$` A GAM is a sum of _smooth functions_ or _smooths_ `$$y_i = \beta_0 + \sum_j \color{red}{s_j(x_{ji})} + \epsilon_i$$` where `\(\epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\)`, `\(y_i \sim \text{Normal}\)` (for now) Call the above equation the **linear predictor** in both cases --- # Fitting a GAM in R GAM needs the package `mgcv`: ```r install.packages("mgcv") library(mgcv) ``` GAM can be calculated with the function `gam()` with requires by default a formula and a data arguments. Method and family are usually important to specify as well. ```r model <- gam(y ~ s(x1) + s(x2) + te(x3, x4), # formuala describing model data = my_data_frame, # your data method = 'REML', # or 'ML' family = gaussian) # or something more exotic ``` `s()` terms are smooths of one or more variables `te()` terms are the smooth equivalent of *main effects + interactions* --- class: inverse background-image: url('./img/rob-potter-398564.jpg') background-size: contain # What magic is this? .footnote[ <a style="background-color:black;color:white;text-decoration:none;padding:4px 6px;font-family:-apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, "San Francisco", "Helvetica Neue", Helvetica, Ubuntu, Roboto, Noto, "Segoe UI", Arial, sans-serif;font-size:12px;font-weight:bold;line-height:1.2;display:inline-block;border-radius:3px;" href="https://unsplash.com/@robpotter?utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=photographer-credit&utm_content=creditBadge" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer" title="Download free do whatever you want high-resolution photos from Rob Potter"><span style="display:inline-block;padding:2px 3px;"><svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" style="height:12px;width:auto;position:relative;vertical-align:middle;top:-1px;fill:white;" viewBox="0 0 32 32"><title></title><path d="M20.8 18.1c0 2.7-2.2 4.8-4.8 4.8s-4.8-2.1-4.8-4.8c0-2.7 2.2-4.8 4.8-4.8 2.7.1 4.8 2.2 4.8 4.8zm11.2-7.4v14.9c0 2.3-1.9 4.3-4.3 4.3h-23.4c-2.4 0-4.3-1.9-4.3-4.3v-15c0-2.3 1.9-4.3 4.3-4.3h3.7l.8-2.3c.4-1.1 1.7-2 2.9-2h8.6c1.2 0 2.5.9 2.9 2l.8 2.4h3.7c2.4 0 4.3 1.9 4.3 4.3zm-8.6 7.5c0-4.1-3.3-7.5-7.5-7.5-4.1 0-7.5 3.4-7.5 7.5s3.3 7.5 7.5 7.5c4.2-.1 7.5-3.4 7.5-7.5z"></path></svg></span><span style="display:inline-block;padding:2px 3px;">Rob Potter</span></a> ] --- class: inverse background-image: url('img/wiggly-things.png') background-size: contain ??? --- # Wiggly things <img src="img/spline-anim.gif" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ??? GAMs use splines to represent the non-linear relationships between covariates, here `x`, and the response variable on the `y` axis. --- # Basis expansions In the polynomial models we used a polynomial basis expansion of `\(\boldsymbol{x}\)` * `\(\boldsymbol{x}^0 = \boldsymbol{1}\)` — the model constant term * `\(\boldsymbol{x}^1 = \boldsymbol{x}\)` — linear term * `\(\boldsymbol{x}^2\)` * `\(\boldsymbol{x}^3\)` * … --- # Splines Splines are *functions* composed of simpler functions Simpler functions are *basis functions* & the set of basis functions is a *basis* When we model using splines, each basis function `\(b_k\)` has a coefficient `\(\beta_k\)` Resultant spline is a the sum of these weighted basis functions, evaluated at the values of `\(x\)` `$$s(x) = \sum_{k = 1}^K \beta_k b_k(x)$$` --- # Splines formed from basis functions <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/basis-functions-1.png" width="767.999664" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ??? Splines are built up from basis functions Here I'm showing a cubic regression spline basis with 10 knots/functions We weight each basis function to get a spline. Here all the basis functions have the same weight so they would fit a horizontal line --- # Weight basis functions ⇨ spline .center[] ??? But if we choose different weights we get more wiggly spline Each of the splines I showed you earlier are all generated from the same basis functions but using different weights --- # How do GAMs learn from data? <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/example-data-figure-1.png" width="767.999664" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ??? How does this help us learn from data? Here I'm showing a simulated data set, where the data are drawn from the orange functions, with noise. We want to learn the orange function from the data --- # Maximise penalised log-likelihood ⇨ β .center[] ??? Fitting a GAM involves finding the weights for the basis functions that produce a spline that fits the data best, subject to some constraints --- class:inverse # Wiggliness `$$\int_{\mathbb{R}} [f^{\prime\prime}]^2 dx = \boldsymbol{\beta}^{\mathsf{T}}\mathbf{S}\boldsymbol{\beta} = \large{W}$$` (Wiggliness is 100% the right mathy word) We penalize wiggliness to avoid overfitting -- `\(W\)` measures **wiggliness** (log) likelihood measures closeness to the data We use a **smoothing parameter** `\(\lambda\)` to define the trade-off, to find the spline coefficients `\(B_k\)` that maximize the **penalized** log-likelihood `$$\mathcal{L}_p = \log(\text{Likelihood}) - \lambda W$$` --- class:inverse # HadCRUT4 time series <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-6-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class:inverse # Picking the right wiggliness .pull-left[ Two ways to think about how to optimize `\(\lambda\)`: * Predictive: Minimize out-of-sample error * Bayesian: Put priors on our basis coefficients ] .pull-right[ Many methods: AIC, Mallow's `\(C_p\)`, GCV, ML, REML * **Practically**, use **REML**, because of numerical stability * Hence `gam(..., method='REML')` ] .center[  ] --- class:inverse # Maximum allowed wiggliness We set **basis complexity** or "size" `\(k\)` This is _maximum wigglyness_, can be thought of as number of small functions that make up a curve Once smoothing is applied, curves have fewer **effective degrees of freedom (EDF)** EDF < `\(k\)` -- `\(k\)` must be *large enough*, the `\(\lambda\)` penalty does the rest *Large enough* — space of functions representable by the basis includes the true function or a close approximation to the tru function Bigger `\(k\)` increases computational cost In **mgcv**, default `\(k\)` values are arbitrary — after choosing the model terms, this is the key user choice **Must be checked!** — `gam.check()` --- # GAM for HadCRUT4 ```r gam_model <- gam( formula = Temperature ~ s(Year), data = gtemp, family = gaussian, method = "REML" ) ``` --- # GAM for HadCRUT4 ```r summary(gam_model) ``` ``` Family: gaussian Link function: identity Formula: Temperature ~ s(Year) Parametric coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) -0.020477 0.009731 -2.104 0.0369 * --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 Approximate significance of smooth terms: edf Ref.df F p-value s(Year) 7.837 8.65 145.1 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 R-sq.(adj) = 0.88 Deviance explained = 88.6% -REML = -91.237 Scale est. = 0.016287 n = 172 ``` --- class: title-slide, middle ## GAM for Spatial Analyses --- # Portugese larks .pull-left[ <table class="table table-striped" style="font-size: 15px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> TET </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> crestlark </th> <th style="text-align:left;"> linnet </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> x </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> y </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> e </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> n </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13883 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> H </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 563000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4665000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 563 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4665 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13893 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> S </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 567000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4665000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 567 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4665 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13877 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> B </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 561000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4663000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 561 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4663 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13887 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> L </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 565000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4663000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 565 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4663 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13881 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> F </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 563000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4661000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 563 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4661 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> 13891 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> Q </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:left;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 567000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4661000 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 567 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4661 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] .pull-right[ <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-10-1.png" width="360" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Portugese larks — binomial GAM ```r gam_model <- gam( formula = crestlark ~ s(e, n, k = 100), data = bird, family = binomial, method = 'REML' ) ``` - `\(s(e, n)\)` indicated by `s(e, n)` in the formula - Isotropic thin plate spline - `k` sets size of basis dimension; upper limit on EDF - Smoothness parameters estimated via REML --- # Portugese larks — binomial GAM ```r summary(gam_model) ``` ``` Family: binomial Link function: logit Formula: crestlark ~ s(e, n, k = 100) Parametric coefficients: Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|) (Intercept) -2.24184 0.07785 -28.8 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 Approximate significance of smooth terms: edf Ref.df Chi.sq p-value s(e,n) 74.04 86.46 857.3 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 R-sq.(adj) = 0.234 Deviance explained = 25.9% -REML = 2499.8 Scale est. = 1 n = 6457 ``` --- # Different types of smooth The type of smoother is controlled by the `bs` argument (think *basis*) The default is a low-rank thin plate spline `bs = 'tp'` Many others available * Cubic splines `bs = 'cr'` * P splines `bs = 'ps'` * Cyclic splines `bs = 'cc'` or `bs = 'cp'` * Adaptive splines `bs = 'ad'` * Random effect `bs = 're'` * Factor smooths `bs = 'fs'` * Duchon splines `bs = 'ds'` * Spline on the sphere `bs = 'sos'` * MRFs `bs = 'mrf'` * Soap-film smooth `bs = 'so'` * Gaussian process `bs = 'gp'` --- # Conditional distributions A GAM is just a fancy GLM Simon Wood & colleagues (2016) have extended the *mgcv* methods to some non-exponential family distributions * `binomial()` * `poisson()` * `Gamma()` * `inverse.gaussian()` * `nb()` * `tw()` * `mvn()` * `multinom()` --- # Smooth interactions Two ways to fit smooth interactions 1. Bivariate (or higher order) thin plate splines * `s(x, z, bs = 'tp')` * Isotropic; single smoothness parameter for the smooth * Sensitive to scales of `x` and `z` 2. Tensor product smooths * Separate marginal basis for each smooth, separate smoothness parameters * Invariant to scales of `x` and `z` * Use for interactions when variables are in different units * `te(x, z)` --- # Tensor product smooths There are multiple ways to build tensor products in *mgcv* 1. `te(x, z)` 2. `t2(x, z)` 3. `s(x) + s(z) + ti(x, z)` `te()` is the most general form but is not compatible with Bayesian analyses `t2()` is an alternative implementation that is compatible with Bayesian analyses `ti()` fits pure smooth interactions; where the main effects of `x` and `z` have been removed from the basis --- # Factor smooth interactions Two ways for factor smooth interactions 1. `by` variable smooths * entirely separate smooth function for each level of the factor * each has it's own smoothness parameter * centred (no group means) so include factor as a fixed effect * `y ~ f + s(x, by = f)` 2. `bs = 'fs'` basis * smooth function for each level of the function * share a common smoothness parameter * fully penalized; include group means * closer to random effects * `y ~ s(x, f, bs = 'fs')` --- # Random effects When fitted with REML or ML, smooths can be viewed as just fancy random effects Inverse is true too; random effects can be viewed as smooths If you have simple random effects you can fit those in `gam()` and `bam()` without needing the more complex GAMM functions `gamm()` or `gamm4::gamm4()` These two models are equivalent ```r m_glme <- glmer(travel ~ Road + (1 | Rail), data = Rail, method = "REML") m_gam <- gam(travel ~ Road + s(Rail, bs = "re"), data = Rail, method = "REML") ``` --- # Random effects The random effect basis `bs = 're'` is not as computationally efficient as *nlme* or *lme4* for fitting * complex random effects terms, or * random effects with many levels Instead see `gamm()` and `gamm4::gamm4()` * `gamm()` fits using `lme()` * `gamm4::gamm4()` fits using `lmer()` or `glmer()` For non Gaussian models use `gamm4::gamm4()` --- class: inverse, mline, center, middle # Model checking --- # Model checking `gam.check()` is essential to check two points in a GAM: - Do you have the right degrees of freedom? - What are the diagnosing model issues? --- # GAMs are models too How accurate your predictions will be depends on how good the model is <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/misspecify-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Simulated data <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/sims_plot-1.png" width="792" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: title-slide, middle ## gam.check() part 1: do you have the right functional form? --- # How well does the model fit? - Set `k` per term - e.g. `s(x, k=10)` or `s(x, y, k=100)` - Penalty removes "extra" wigglyness - *up to a point!* - (But computation is slower with bigger `k`) --- # Checking basis size ```r norm_model_1 <- gam( y_norm ~ s(x1, k = 4) + s(x2, k = 4), method = 'REML' ) gam.check(norm_model_1) ``` ``` Method: REML Optimizer: outer newton full convergence after 8 iterations. Gradient range [-0.0003467788,0.0005154578] (score 736.9402 & scale 2.252304). Hessian positive definite, eigenvalue range [0.000346021,198.5041]. Model rank = 7 / 7 Basis dimension (k) checking results. Low p-value (k-index<1) may indicate that k is too low, especially if edf is close to k'. k' edf k-index p-value s(x1) 3.00 1.00 0.13 <0.0000000000000002 *** s(x2) 3.00 2.91 1.04 0.83 --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- # Checking basis size ```r norm_model_2 <- gam( y_norm ~ s(x1, k = 12) + s(x2, k = 4), method = 'REML' ) gam.check(norm_model_2) ``` ``` Method: REML Optimizer: outer newton full convergence after 11 iterations. Gradient range [-0.000005658609,0.000005392657] (score 345.3111 & scale 0.2706205). Hessian positive definite, eigenvalue range [0.967727,198.6299]. Model rank = 15 / 15 Basis dimension (k) checking results. Low p-value (k-index<1) may indicate that k is too low, especially if edf is close to k'. k' edf k-index p-value s(x1) 11.00 10.84 0.99 0.38 s(x2) 3.00 2.98 0.86 0.01 ** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- # Checking basis size ```r norm_model_3 <- gam( y_norm ~ s(x1, k = 12) + s(x2, k = 12), method = 'REML' ) gam.check(norm_model_3) ``` ``` Method: REML Optimizer: outer newton full convergence after 8 iterations. Gradient range [-0.00000001136212,0.0000000000006723511] (score 334.2084 & scale 0.2485446). Hessian positive definite, eigenvalue range [2.812271,198.6868]. Model rank = 23 / 23 Basis dimension (k) checking results. Low p-value (k-index<1) may indicate that k is too low, especially if edf is close to k'. k' edf k-index p-value s(x1) 11.00 10.85 0.98 0.31 s(x2) 11.00 7.95 0.95 0.15 ``` --- # Checking basis size <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-18-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: title-slide, middle ## Using gam.check() part 2: visual checks --- # gam.check() plots `gam.check()` creates 4 plots: 1. Quantile-quantile plots of residuals. If the model is right, should follow 1-1 line 2. Histogram of residuals 3. Residuals vs. linear predictor 4. Observed vs. fitted values `gam.check()` uses deviance residuals by default --- # Gaussian data, Gaussian model ```r norm_model <- gam( y_norm ~ s(x1, k=12) + s(x2, k=12), method = 'REML' ) gam.check(norm_model, rep = 500) ``` <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-19-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Negative binomial data, Poisson model ```r pois_model <- gam( y_negbinom ~ s(x1, k=12) + s(x2, k=12), family = poisson, method = 'REML' ) gam.check(pois_model, rep = 500) ``` <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-20-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # NB data, NB model ```r negbin_model <- gam( y_negbinom ~ s(x1, k=12) + s(x2, k=12), family = nb, method = 'REML' ) gam.check(negbin_model, rep = 500) ``` <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-21-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: title-slide, middle ## *p* values for smooths --- # *p* values for smooths *p* values for smooths are approximate: 1. they don't account for the estimation of `\(\lambda_j\)` — treated as known, hence *p* values are biased low 2. rely on asymptotic behaviour — they tend towards being right as sample size tends to `\(\infty\)` --- # *p* values for smooths ...are a test of **zero-effect** of a smooth term Default *p* values rely on theory of Nychka (1988) and Marra & Wood (2012) for confidence interval coverage If the Bayesian CI have good across-the-function properties, Wood (2013a) showed that the *p* values have - almost the correct null distribution - reasonable power Test statistic is a form of `\(\chi^2\)` statistic, but with complicated degrees of freedom --- # *p* values for smooths Have the best behaviour when smoothness selection is done using **ML**, then **REML**. Neither of these are the default, so remember to use `method = "ML"` or `method = "REML"` as appropriate --- # AIC for GAMs - Comparison of GAMs by a form of AIC is an alternative frequentist approach to model selection - Rather than using the marginal likelihood, the likelihood of the `\(\mathbf{\beta}_j\)` *conditional* upon `\(\lambda_j\)` is used, with the EDF replacing `\(k\)`, the number of model parameters - This *conditional* AIC tends to select complex models, especially those with random effects, as the EDF ignores that `\(\lambda_j\)` are estimated - Wood et al (2016) suggests a correction that accounts for uncertainty in `\(\lambda_j\)` `$$AIC = -2\mathcal{L}(\hat{\beta}) + 2\mathrm{tr}(\widehat{\mathcal{I}}V^{'}_{\beta})$$` --- class: title-slide, middle ## Exercise 1: Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> Using R, analyse a generalised additive mixed model with the data from `gamair::co2s` <div class="countdown" id="timer_80c0ee1c" data-warn-when="60" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="right:0;bottom:0;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">05</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> .pull-left[ ```r #install.packages("gamair") library(gamair) data(co2s) head(co2s, n = 20) |> kable() ``` <table> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> co2 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> c.month </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> month </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 313.21 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 313.71 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 314.31 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 14 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 314.13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 16 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 17 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 314.36 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 18 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 19 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> NA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] .pull-right[ <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-24-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> — fit naive GAM ```r b <- gam( co2 ~ s(c.month), data = co2s, method = 'REML' ) summary(b) ``` ``` Family: gaussian Link function: identity Formula: co2 ~ s(c.month) Parametric coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) 338.24515 0.02289 14774 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 Approximate significance of smooth terms: edf Ref.df F p-value s(c.month) 8.821 8.991 45117 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 R-sq.(adj) = 0.999 Deviance explained = 99.9% -REML = 311.46 Scale est. = 0.22382 n = 427 ``` --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> — predict Predict the next 36 months <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> — better model Decompose into 1. a seasonal smooth 2. a long term trend ```r b2 <- gam( co2 ~ s(month) + s(c.month), data = co2s, method = 'REML' ) ``` --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> — better model .smaller[ ```r summary(b2) ``` ``` Family: gaussian Link function: identity Formula: co2 ~ s(month) + s(c.month) Parametric coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) 338.24515 0.01307 25877 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 Approximate significance of smooth terms: edf Ref.df F p-value s(month) 6.936 8.025 107.5 <0.0000000000000002 *** s(c.month) 8.943 8.999 137605.9 <0.0000000000000002 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 R-sq.(adj) = 1 Deviance explained = 100% -REML = 90.217 Scale est. = 0.072954 n = 427 ``` ] --- # Atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> — predict <img src="lecture_4_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-27-1.png" width="504" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: title-slide, middle ## Exercise 2 - Load the `mgcv` package and the `mgcv::gam.test` dataset. Fit a GAM to predict the `y` variable using the `x` variable, and plot the fitted curve. <div class="countdown" id="timer_513275ad" data-warn-when="60" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="right:0;bottom:0;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">03</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- class: title-slide, middle ## Exercise 3 - Load the `mgcv::visco` dataset. Fit a GAM to predict the `stress` variable using the `strain` variable. <div class="countdown" id="timer_544e7a25" data-warn-when="60" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="right:0;bottom:0;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">03</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- class: title-slide, middle ## Exercise 4 - Load the `mgcv::gala` dataset. Fit a GAM to predict the `log.sp` variable using the `depth` variable, and include a smoothing term for the `region` variable. <div class="countdown" id="timer_89eb1f8f" data-warn-when="60" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="right:0;bottom:0;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">03</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- class: title-slide, middle ## Exercise 5 - Load the `mgcv::airquality` dataset. Fit a GAM to predict the `Ozone` variable using the `Temp` and `Wind` variables, and include a smoothing term for the `Month` variable. <div class="countdown" id="timer_3c3a3b25" data-warn-when="60" data-update-every="1" tabindex="0" style="right:0;bottom:0;"> <div class="countdown-controls"><button class="countdown-bump-down">−</button><button class="countdown-bump-up">+</button></div> <code class="countdown-time"><span class="countdown-digits minutes">03</span><span class="countdown-digits colon">:</span><span class="countdown-digits seconds">00</span></code> </div> --- class: inverse, mline, left, middle <img class="circle" src="https://github.com/damien-dupre.png" width="250px"/> # Thanks for your attention and don't hesitate if you have any questions! - [<svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M459.37 151.716c.325 4.548.325 9.097.325 13.645 0 138.72-105.583 298.558-298.558 298.558-59.452 0-114.68-17.219-161.137-47.106 8.447.974 16.568 1.299 25.34 1.299 49.055 0 94.213-16.568 130.274-44.832-46.132-.975-84.792-31.188-98.112-72.772 6.498.974 12.995 1.624 19.818 1.624 9.421 0 18.843-1.3 27.614-3.573-48.081-9.747-84.143-51.98-84.143-102.985v-1.299c13.969 7.797 30.214 12.67 47.431 13.319-28.264-18.843-46.781-51.005-46.781-87.391 0-19.492 5.197-37.36 14.294-52.954 51.655 63.675 129.3 105.258 216.365 109.807-1.624-7.797-2.599-15.918-2.599-24.04 0-57.828 46.782-104.934 104.934-104.934 30.213 0 57.502 12.67 76.67 33.137 23.715-4.548 46.456-13.32 66.599-25.34-7.798 24.366-24.366 44.833-46.132 57.827 21.117-2.273 41.584-8.122 60.426-16.243-14.292 20.791-32.161 39.308-52.628 54.253z"/></svg> @damien_dupre](http://twitter.com/damien_dupre) - [<svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 496 512" style="height:1em;width:0.97em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M165.9 397.4c0 2-2.3 3.6-5.2 3.6-3.3.3-5.6-1.3-5.6-3.6 0-2 2.3-3.6 5.2-3.6 3-.3 5.6 1.3 5.6 3.6zm-31.1-4.5c-.7 2 1.3 4.3 4.3 4.9 2.6 1 5.6 0 6.2-2s-1.3-4.3-4.3-5.2c-2.6-.7-5.5.3-6.2 2.3zm44.2-1.7c-2.9.7-4.9 2.6-4.6 4.9.3 2 2.9 3.3 5.9 2.6 2.9-.7 4.9-2.6 4.6-4.6-.3-1.9-3-3.2-5.9-2.9zM244.8 8C106.1 8 0 113.3 0 252c0 110.9 69.8 205.8 169.5 239.2 12.8 2.3 17.3-5.6 17.3-12.1 0-6.2-.3-40.4-.3-61.4 0 0-70 15-84.7-29.8 0 0-11.4-29.1-27.8-36.6 0 0-22.9-15.7 1.6-15.4 0 0 24.9 2 38.6 25.8 21.9 38.6 58.6 27.5 72.9 20.9 2.3-16 8.8-27.1 16-33.7-55.9-6.2-112.3-14.3-112.3-110.5 0-27.5 7.6-41.3 23.6-58.9-2.6-6.5-11.1-33.3 2.6-67.9 20.9-6.5 69 27 69 27 20-5.6 41.5-8.5 62.8-8.5s42.8 2.9 62.8 8.5c0 0 48.1-33.6 69-27 13.7 34.7 5.2 61.4 2.6 67.9 16 17.7 25.8 31.5 25.8 58.9 0 96.5-58.9 104.2-114.8 110.5 9.2 7.9 17 22.9 17 46.4 0 33.7-.3 75.4-.3 83.6 0 6.5 4.6 14.4 17.3 12.1C428.2 457.8 496 362.9 496 252 496 113.3 383.5 8 244.8 8zM97.2 352.9c-1.3 1-1 3.3.7 5.2 1.6 1.6 3.9 2.3 5.2 1 1.3-1 1-3.3-.7-5.2-1.6-1.6-3.9-2.3-5.2-1zm-10.8-8.1c-.7 1.3.3 2.9 2.3 3.9 1.6 1 3.6.7 4.3-.7.7-1.3-.3-2.9-2.3-3.9-2-.6-3.6-.3-4.3.7zm32.4 35.6c-1.6 1.3-1 4.3 1.3 6.2 2.3 2.3 5.2 2.6 6.5 1 1.3-1.3.7-4.3-1.3-6.2-2.2-2.3-5.2-2.6-6.5-1zm-11.4-14.7c-1.6 1-1.6 3.6 0 5.9 1.6 2.3 4.3 3.3 5.6 2.3 1.6-1.3 1.6-3.9 0-6.2-1.4-2.3-4-3.3-5.6-2z"/></svg> @damien-dupre](http://github.com/damien-dupre) - [<svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 640 512" style="height:1em;width:1.25em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M579.8 267.7c56.5-56.5 56.5-148 0-204.5c-50-50-128.8-56.5-186.3-15.4l-1.6 1.1c-14.4 10.3-17.7 30.3-7.4 44.6s30.3 17.7 44.6 7.4l1.6-1.1c32.1-22.9 76-19.3 103.8 8.6c31.5 31.5 31.5 82.5 0 114L422.3 334.8c-31.5 31.5-82.5 31.5-114 0c-27.9-27.9-31.5-71.8-8.6-103.8l1.1-1.6c10.3-14.4 6.9-34.4-7.4-44.6s-34.4-6.9-44.6 7.4l-1.1 1.6C206.5 251.2 213 330 263 380c56.5 56.5 148 56.5 204.5 0L579.8 267.7zM60.2 244.3c-56.5 56.5-56.5 148 0 204.5c50 50 128.8 56.5 186.3 15.4l1.6-1.1c14.4-10.3 17.7-30.3 7.4-44.6s-30.3-17.7-44.6-7.4l-1.6 1.1c-32.1 22.9-76 19.3-103.8-8.6C74 372 74 321 105.5 289.5L217.7 177.2c31.5-31.5 82.5-31.5 114 0c27.9 27.9 31.5 71.8 8.6 103.9l-1.1 1.6c-10.3 14.4-6.9 34.4 7.4 44.6s34.4 6.9 44.6-7.4l1.1-1.6C433.5 260.8 427 182 377 132c-56.5-56.5-148-56.5-204.5 0L60.2 244.3z"/></svg> damien-datasci-blog.netlify.app](https://damien-datasci-blog.netlify.app) - [<svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M501.6 4.186c-7.594-5.156-17.41-5.594-25.44-1.063L12.12 267.1C4.184 271.7-.5037 280.3 .0431 289.4c.5469 9.125 6.234 17.16 14.66 20.69l153.3 64.38v113.5c0 8.781 4.797 16.84 12.5 21.06C184.1 511 188 512 191.1 512c4.516 0 9.038-1.281 12.99-3.812l111.2-71.46l98.56 41.4c2.984 1.25 6.141 1.875 9.297 1.875c4.078 0 8.141-1.031 11.78-3.094c6.453-3.625 10.88-10.06 11.95-17.38l64-432C513.1 18.44 509.1 9.373 501.6 4.186zM369.3 119.2l-187.1 208.9L78.23 284.7L369.3 119.2zM215.1 444v-49.36l46.45 19.51L215.1 444zM404.8 421.9l-176.6-74.19l224.6-249.5L404.8 421.9z"/></svg> damien.dupre@dcu.ie](mailto:damien.dupre@dcu.ie)